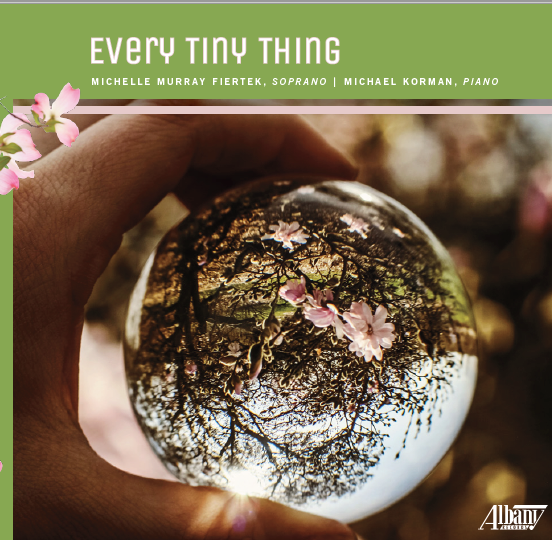

Every Tiny Thing (Albany Records, 2020)

What does American art song sound like?

The art song tradition has deep roots in Western Europe, particularly in France, Germany, and England. Each of these nations has cultivated a sound within the genre as distinct as its language. What they share is an appreciation for the intimate and intellectual nature of song, which traditionally requires only a piano, a singer, a poem, and an imaginative composer. The United States, though a perennial trendsetter in geopolitical matters, has lagged in developing a homegrown art song tradition as part of a unique classical sound. Its reluctance is rooted in attributes that distinguish America from European nations; namely, its vastness and its multicultural composition. It is heterogenous by every measure, offering a considerable challenge to any single artist attempting to represent America as a people.

When the Czech composer Antonin Dvořák took up residency in New York in the 1890’s, he observed America from the vantage point of so many of its residents: as an immigrant in search of greater opportunity. He wrote extensively about America’s singular virtues and the potential of its musical legacy. His Symphony No. 9, “From the New World,” premiered in New York to enormous acclaim, and presented a fresh palette of sounds evoking the American spirit. Dvořák, and visionary successors like Copland, Ives, Barber, and Bernstein, built a foundation on which all forms of American classical music could prosper. In the mid-twentieth century, the composer Roy Harris wrote songs that blended seemingly incongruous elements of the European tradition: folk melodies with orchestral accompaniment, set to the verse of esteemed American poets like Walt Whitman. In the decades since, William Bolcom’s songs have invoked pop, jazz, and ragtime, proudly rejecting the idea of intellectual divisions among different musical traditions. American art song eagerly and purposefully became a melting pot of its own, and today, its legacy is as legitimate as any other nation’s. The modern catalog of American song is laced with Dvořák’s optimism and imbued with national pride. It spans the works of early trailblazers like Ives, Bacon, Fine, Duke, and Hoiby, to vibrant voices of the twenty-first century, like Harbison, Larsen, Heggie, Musto, Laitman, and Hall, in addition to the composers represented on this album. It is a celebration of the pioneer spirit in music that overcame centuries of self-doubt.

On her new album, Every Tiny Thing, Michelle Fiertek presents a collection of songs lovingly grown in this new American tradition, which audibly draw influence from domestic genres like folk and musical theatre. The diverse selection of poetry channels American landscapes, both great and small—the tameless West, the impressionistic seasons of New England, the gentle hills of Appalachia, the miles of rugged coastline that withstand daily lashings from two oceans. These images illustrate not only America’s unique topography, but a steadfast cultural appreciation of its singularity.

The truest testaments to how far American art song has come may be found in “Every Tiny Thing” and “Love’s Astronomy.” The former is a loving antidote to our proclivity for constant activity, reminding us to savor the smallest, most ephemeral pleasures. The latter is a concise but powerful love letter that invokes America’s towering scientific achievement: its journey to the stars. Together, these songs draw the spectrum of great American traditions—from stopping to notice little wonders, to looking beyond where anyone else has ever ventured.

—Emily Rose Walsh

The notes for this album begin with a question: “What does American art song sound like?”, and in the program it is easy to see and hear this question answered, this music painting portraits of different parts of America along the way. The texts to these works sometimes even suggest these American spaces literally, such as “I placed a jar in Tennessee/ And round it was, on a hill./It made the slovenly wilderness/Surround that hill” (the emotional, almost sorrowful Anecdote of the Jar by Benjamin Yarmolinsky with text by Wallace Stevens), and in Richard Pearson Thomas’s ‘When I Kiss You’: “When I Kiss You/I see the hills of Montana rolling before my eyes/and I’m driving home again beneath that big Big sky”. The album is named after David Wolfson’s Every Tiny Thing, whose text and tones bear gem-like moments aplenty. The disc title comes from these lines: “I am like a moth who circles in its flight for love of light./I am like ev’ry tiny thing that needs to move, and grow, and strive/and feels delight in knowing it’s alive.” This album is a wonderful presentation of these pieces of America that meet at the intersection of art song and folk song and popular song, and soprano Michelle Murray Fiertek and pianist Michael Korman deserve a hefty round of applause for this effort.

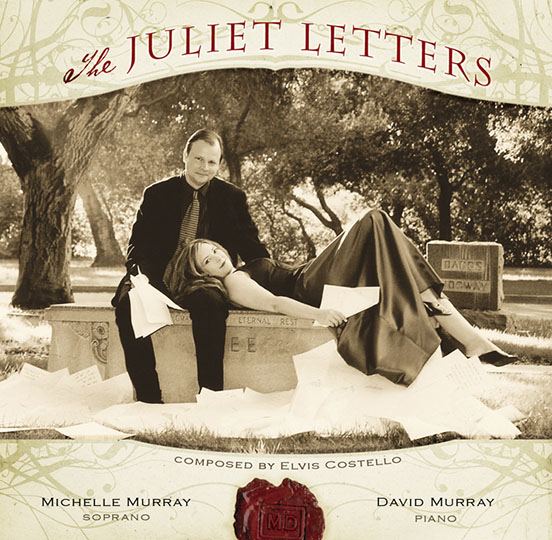

The Juliet Letters (Summit Records, 2006)

Music by Elvis Costello & The Brodsky Quartet

Arranged for Piano by David Murray

In the liner notes to his original 1992 recording of The Juliet Letters, Elvis Costello wrote that he had come across a newspaper article detailing the exploits of an unknown Veronese professor who had assumed the responsibility of anonymously responding to letters written to Juliet Capulet. This, he writes, “apparently continued for a number of years, until some gentlemen of the press exposed this secret correspondence.”

Costello’s story has all the makings of a classic urban legend: a nameless man works in secret to answer letters addressed to a dead fictional character until he is at some point unmasked by (again unnamed) members of the press. This version, mysterious and sexy, makes for great reading but leaves a lot of questions unanswered: how did the professor get the letters in the first place? Didn’t the postman delivering them to him notice that they were addressed to “Juliet?” Did anyone wonder about the high volume of mail that must have been entering and exiting his home? How did he, on an academic’s salary, afford all those postage stamps?

Nevertheless, it’s still a good tale, and one that I’ve told to many audiences before performing these songs. Over the years, I’ve even added my own touches: that the professor would visit the tomb in the darkest hours of every night, collecting the letters secretly by candlelight; that he continued responding to these letters until his death, at which time his family revealed that he was the one who, for decades, had been corresponding with the world; that in his dead hands was found one final letter, still in its sealed envelope, that must forever remain unopened and unanswered.

The truth behind the legend is less exotic, but by no means pedestrian. In 1935 (or 1937, depending on who you believe), Antonio Avena, the Director of the Verona Civic Museums, opened the thirteenth-century cloisters of the Capuccinni monastery of San Francesco al Corso to the public. In order to increase tourist activity, he called the cloisters “Juliet’s tomb,” part of a sightseeing triumvirate (along with “Juliet’s House” and “Romeo’s House,” both conveniently located nearby). Although the empty sarcophagus that sits in the middle of the tomb had probably been identified as Juliet’s gravesite at the beginning of the nineteenth century, Avena was the first to mass-market the cloisters under that name.

Shortly afterward, in 1937 (or 1938), a letter arrived in Verona, Italy, addressed to Juliet Capulet. For unknown reasons, the curator of Juliet’s tomb wrote back, sparking a trend that would eventually spread throughout the world. Over the ensuing years so many letters continued to arrive for Juliet that the city of Verona organized the Juliet Club in 1990, an organization with a team of eight volunteer secretaries who respond to the more than 5000 letters that are received each year. Although we don’t know exactly what the letters to Juliet contain, I like to think of the writers asking for advice, discussing problems or issues with life that they can’t talk about with even their closest friends, or even offering prayers — as to a saint.

Whatever the truth about the origins of the Juliet letters, Costello and the Brodsky Quartet were inspired by the idea of this correspondence and jointly composed 17 songs for voice and string quartet that explore the types of letters that might have been left at Juliet’s tomb.

When I first heard the original recording of these pieces in 1995, I was immediately struck by how clever, witty, and compelling they were. It wasn’t long after my first listening to that recording that I decided to arrange these songs for piano and voice, enabling myself to perform them instead of just passively listening to them.

Flash forward eight years: after recording Blue, Michelle and I took a trip to San Diego to celebrate. On the way home, we started talking about what our next recording should be. I mentioned my desire to arrange the Juliet Letters and played her the CD. We listened to the songs for the entire six hour drive. After a few times through the entire disc, we knew we had found our next project.

Right away, I began arranging the songs and was struck by the difficulty of transferring the original accompaniments from string quartet to piano. The original arrangements are masterpieces of understated, almost minimalistic, part writing; many of the songs consist solely of chains of successive triads that weave hypnotically underneath the vocal line. Although this approach works very well with string accompaniment, piano accompaniment is, by necessity, a totally different animal.

I soon decided that it was more important to keep the original emotional intent underlying the songs intact rather than transcribing the original string parts note-for-note to the piano. Once I reached this decision, the act of arranging (or, in some cases, composing) became much more natural and organic. Although I was able, in certain songs, to keep my arrangement very similar to the original, most songs have a completely recomposed accompaniment.

One troubling aspect of arranging these songs was determining exactly what they were. What genre of music could they be categorized as? Are they pop music or classical music? Should they be tonal, atonal, or merely dissonant? I kept two handwritten sentences on a piece of paper with me and would refer to them every time I started to work on a new song. The first, written by Costello himself in the original Juliet Letters liner notes, simply says, “This is no more my stab at ‘classical music’ than it is the Brodsky Quartet’s first rock and roll album.” The second was something Charles Ives wrote in 1925: “Why tonality as such should be thrown out for good, I can’t see. Why it should be always present, I can’t see. It depends, it seems to me, a good deal – as clothes depend on the thermometer – on what one is trying to do.” Buttressed by this wisdom, I began to listen to each song as if for the first time, letting go of my preformed opinions. I let the text and expressive content of each song determine its own style. Although different than the composers’ original conception, my goal has been to remain true to their intent.

David Murray, 2006

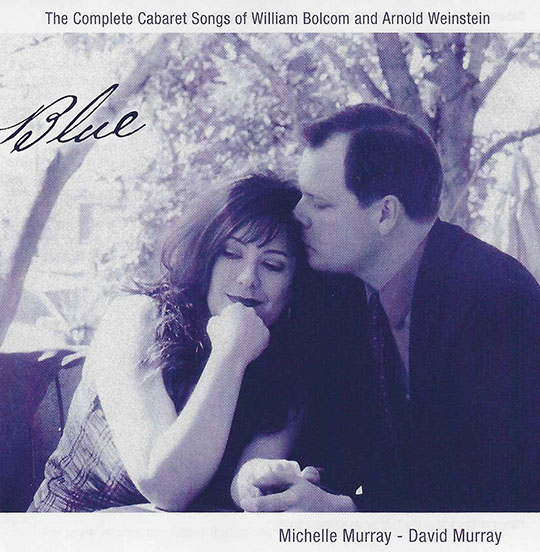

Blue (Summit Records, 2003)

The Complete Cabaret Songs of

William Bolcom and Arnold Weinstein

Michelle and David Murray bring their talent for musical collaboration to the international recording scene with their album Blue: The Complete Cabaret Songs of William Bolcom and Arnold Weinstein. William Bolcom, a member of the faculty of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is a 1988 Pulitzer Prize winner. This recording is the FIRST to include all twenty-four of Bolcom’s Cabaret Songs.

The Cabaret Songs are intriguing and accessible late twentieth-century compositions for mezzo-soprano and piano. They blend classical and popular styles and constitute a significant contribution to the American art song genre. This collection contains portraits of fanciful characters such as a self-absorbed girl whose beauty disrupts everything around her, a smarmy poseur intent on seducing every woman he meets, and a cross-dressing opera singer whose untimely death is remembered over cocktails. These pieces also contain vivid depictions of every day life, such as the painful breakup of a marriage and the loving bond between father and child.